“How would a giant solar panel system on the border wall affect electricity prices throughout southern Texas”

(Kevin O’Brien)

Donald Trump said Mexico was going to pay for the wall. Then he said Mexico would be paying “at a later date so we can get started early.” Now it looks like America’s southern neighbor might not have to pay anything at all. The sun could foot the bill.

One of the President’s core campaign promises is projected to come at a high price. Preliminary cost estimates for a 2,000-mile border wall between the United States and Mexico easily total billions of dollars. One February report from the Department of Homeland Security put the price tag at around $21.6 billion. Democratic staffers in the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs wrote a couple months later how costs could scale up to $70 billion.

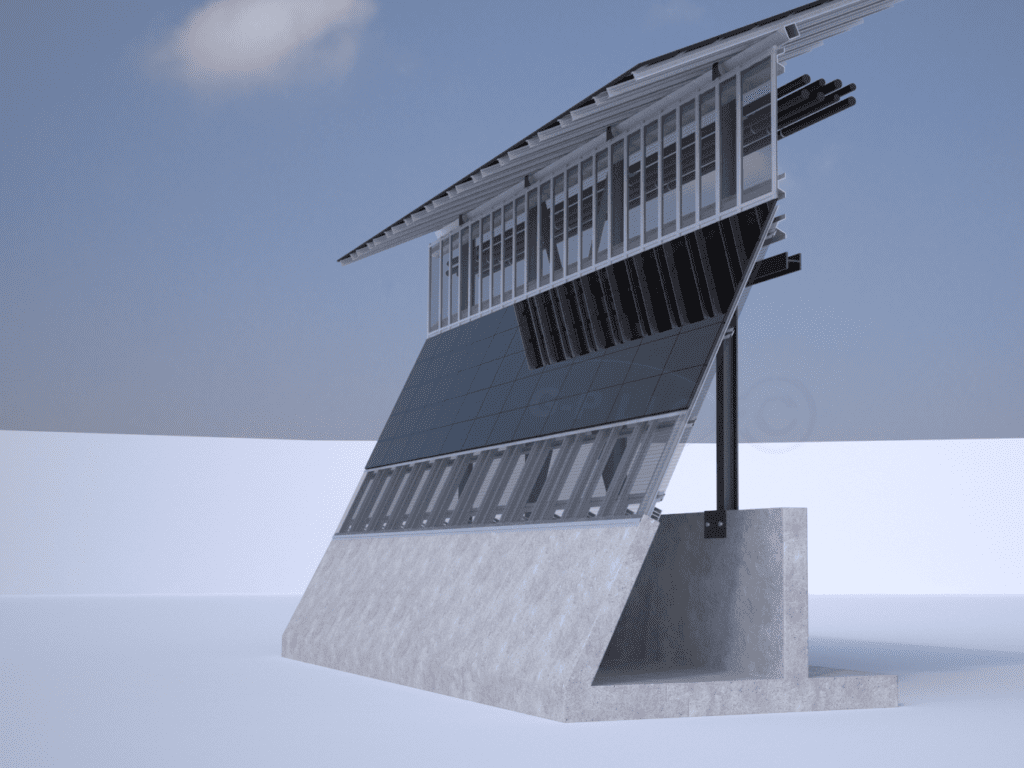

Interested companies had until early April to submit border wall designs to the government for review. One of the proposals pitched the idea of adding solar panels to the wall as a way to generate revenue. The company, Gleason Partners LLC, said panels on sections of the wall (equipped with a moveable array to track the sun) would recoup the cost of construction in 20 years. They said power could be sold to utility providers in the US and Mexico.

The president floated the idea of equipping the wall with solar panels to mitigate costs in a Congressional meeting in June.

Some believe solar panels on the wall could help drive down electricity prices for states in the southwest. This idea isn’t too far-fetched. A team from PowerScout, a company whose employees have aided in the financing and development of over $750 million in solar projects, estimated a solar wall could churn out enough power for 9.2 million homes if the panels hit their normal 25-year lifespan. At today’s wholesale prices, PowerScout projects about $169 billion dollars in generated electricity. This could be a huge boon to those hoping for more competitive electricity prices.

Other solar companies also believe equipping the wall with panels could reap big benefits in regards to power. Thanks to the high amount of sun on the border, Elemental Energy said 10-foot high paneling would create about 7.28 gigawatt- hours of electricity each day. Executives like Jigar Shah at Generate Capital, suggests panels could generate about 6,600 gigawatt-hours each year, while consultant Adam Siegal projects about 8,432 gigawatt-hours annually. This much electricity surging into infrastructure and through utility companies could very well lead to cheaper prices for power.

PowerScout also looked into construction figures by using publically available data, and compared their findings with projections from Gleason Partners. Based on the cost of solar panels, they say it would actually take about 25 years for the wall to pay for itself. However, that number doesn’t necessarily take into account factors like additional financing expenses, buying land, building transmission lines, or panel maintenance. PowerScout also found Gleason’s estimated building cost of $7.2 million dollars per mile was “virtually impossible to achieve with any set of assumptions.” According to government figures, the $7.2 million figure would be about the price of a simple fence.

PowerScout estimated the cost of adding solar panels alone to the wall would total about $46 million dollars per mile. That would mean a solar-equipped border wall would end up at around $68-$158 billion dollars right now.

According to PowerScout, Gleason’s construction plans also fall short of being an economical way to generate solar power. Company analysis said their projected two-tiered solar structure would be about 25% more expensive than just building solar farms.

The founder of Gleason Partners rejected the conclusions by PowerScout.

Tom Gleason said he was sure that PowerScout failed to conduct a thorough review of their design. He explained how his company’s plans included efficient construction methods like “thin-film modules” that were not accounted for by PowerScout. According to him, the wall “is designed by experts and common sense.”

Equipping the wall with solar panels could be lucrative for those hoping for cheaper electricity. The sheer amount of power that could be produced would no doubt affect local electricity markets across the American southwest. However, the high upfront construction costs might not make a solar powered wall a practical avenue for cheaper electricity, especially as opposed to other alternatives.